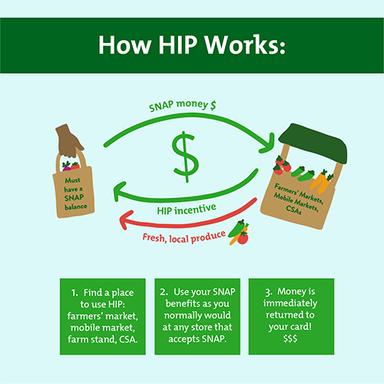

By Contributing Writer; Aimee Whittington Ph.D. Growing evidence shows that farmers’ markets reduce food insecurity, and thus risk of hunger. They do so by generating social capital, promoting healthy food utilization and consumption, and increasing healthy food access in target communities. Additionally, many markets are recognizing a growing role in anti-hunger work. Definitions of food security vary but the most widely accepted definition is “a situation that exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) Partnerships between nonprofit area food banks and local farmers’ markets provide opportunities to distribute the maximum social and nutritional benefits of farmers’ markets. Traditionally and still too often, an experience afforded overwhelmingly to middle- and high-income consumers. Aligning farmers’ markets with food banks generates opportunities for markets to serve low-income customers and fight hunger where it begins. Building social capital in a community has become increasingly important, with the evolution of social media. Broadly defined, social capital is “the value of social networks, bonding similar people and bridging between diverse people, with norms of reciprocity”. With regard to fighting hunger, social capital is central to food security. More of the former leads to greater chance of the latter. Social safety nets/supports and connected communities increase household resilience to economic and environmental stressors. While social exclusion or deprivation greatly increase rates of food insecurity. Surveys of farmers’ markets show that social interaction and community-building are important reasons for attendance, on the part of both customers and vendors. Farmers’ markets empower food insecure customers to consume healthy food, via formal and informal education programs and incentives. Markets provide a setting for community members to gain the knowledge, confidence, and desire required to choose and prepare a variety of (often unfamiliar/region-specific) fruits and vegetables. When asked, market visitors overwhelmingly report positively affected attitudes towards ‘healthy food’ consumption. And studies show well over 50% of regur farmers’ market patrons report eating more fruits and vegetables because of their attendance. By incorporating educational materials, markets working with nonprofits that target low income consumers, can assist customer learning and positively affect the attitudes towards healthy food choices. In addition to changing customer attitudes, farmers’ markets can increase access to nutritious food. Strategic placements of markets in locations frequented by target populations can increase geographic access to healthy food. By partnering with local food banks, farmers’ markets provide access to products normally inaccessible to food bank patrons. Based on national SNAP and WIC enrollment, farmers’ markets are not convenient to low-income community members. Over half of the people using a federal benefit had to travel over 30 minutes to reach the market, with half of those having to utilize public transport. Partnerships between farmers’ markets and food banks work especially well because of the food bank itself, which hosts many low-income clients. The influence of farmers’ markets in general, and those in Massachusetts with respect to the Healthy Incentives Program in particular, on economic access to food is quite clear. By encouraging all vendors to accept SNAP, WIC, and WIC and Senior FMNP food assistance, markets increase the number of food insecure and/or low-income customers who have access to healthy food. Markets at which eligible vendors accept food assistance benefits have, overwhelmingly and for ALL transaction types - higher sales. Additionally, SNAP and matching incentive programs have brought new customers and new revenue to markets across the country. Depending on the city, between 25-60% of new market customers surveyed cited them as a reason for attending. When farmers’ markets generate income and influence market forces at vendors’ booths and beyond, they can increase their community’s overall economic and food security. The “social atmosphere” of farmers’ markets encourages small business and entrepreneurial growth, in addition to developing business management skills in growing enterprises. They can be used to build supportive social networks, while promoting a strong local economy, creating income for small producer. Not only does aligning farmers’ markets with local nonprofit food banks create opportunities for low-income communities to combat food insecurity, it also cultivates small business growth, as a return on investment to community.

0 Comments

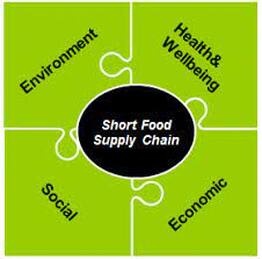

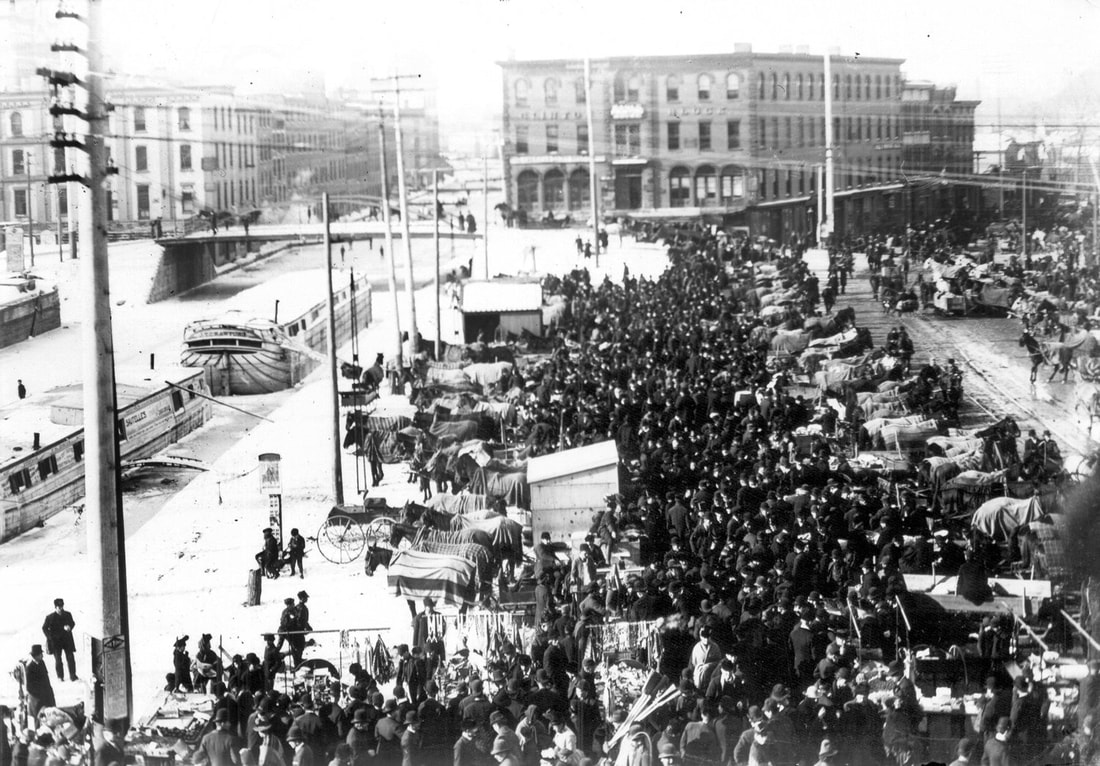

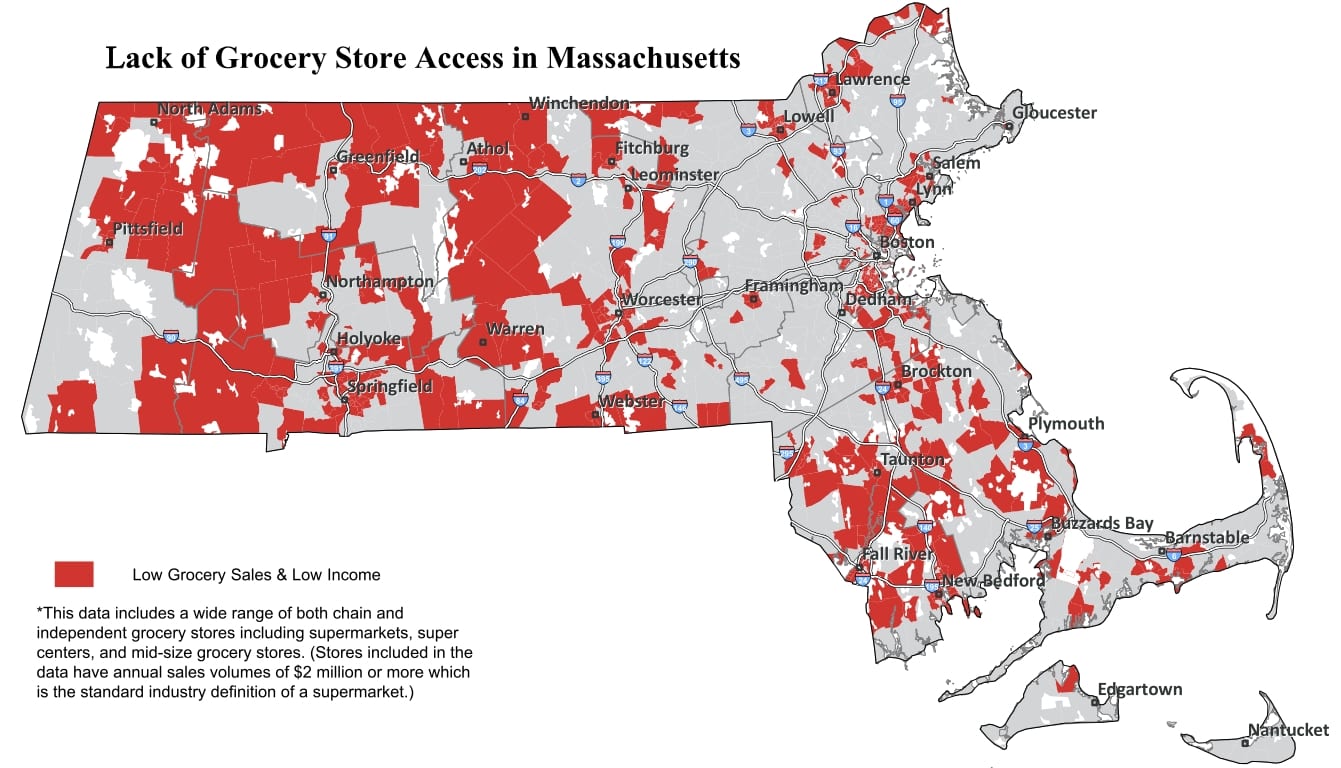

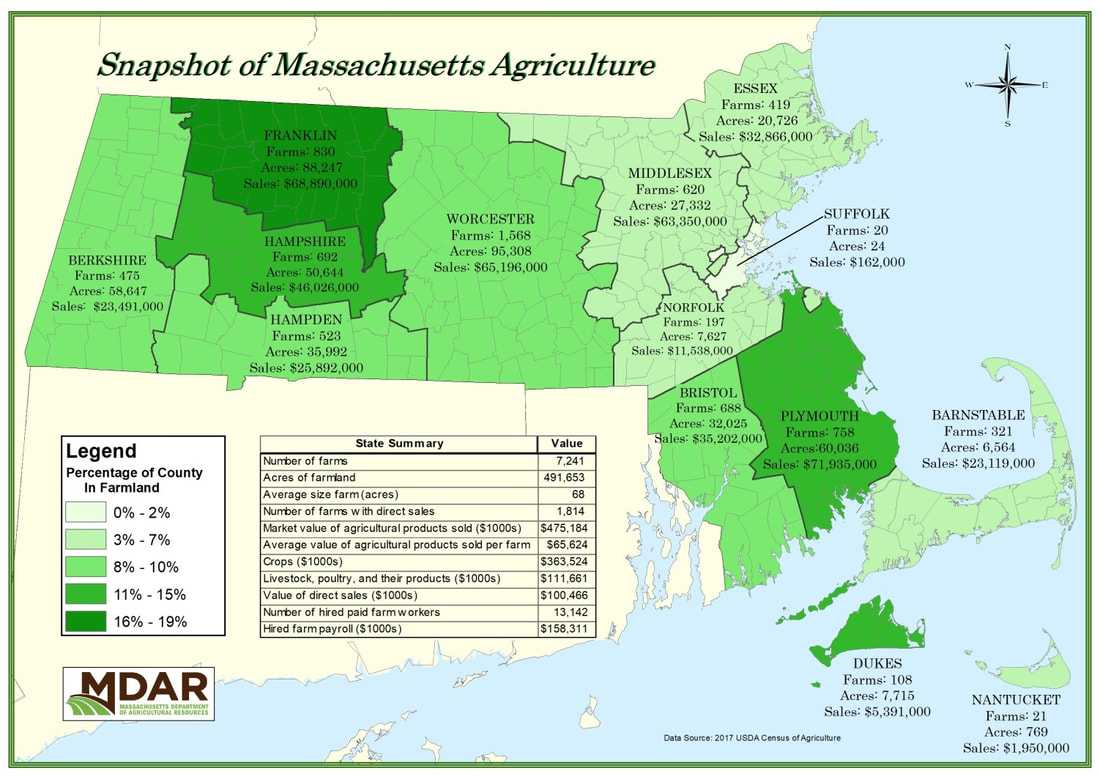

By Contributing Writer; Aimee Whittington Ph.D. Farmers’ markets have a long and multi-faceted history, existing in one form or another for over 5,000 years. Originating in Egypt, the farmers growing in the fertile Nile River Valley came together to sell their products. Unlike modern American farmers’ markets, which are usually held weekly, Egyptian markets took place daily. Each city had a centralized market, selling not only food but supplies and crafts, as well. Some of the products would have looked quite different, such as barley, flax and live animals but the framework is the same. Interestingly, ancient Egyptian markets operated on a trade or barter basis, as the people did not use money. Customers brought finished homemade items made from market goods to barter for necessary supplies. Most exchanges were based on the deben (roughly 3 ounces), an Egyptian unit of measurement. Purchases were placed on one side of a scale and debens added to the other until the scale balanced. This process helped keep trading fair. Massachusetts boasts the first recorded farmers’ market in the United States. Held in Boston, it opened in 1634. appeared in Boston in 1634. 9 other New England markets were up and running by 1700. As the colonies and their cities expanded, so did the need for a consistent supply of foodstuffs and other products. It makes sense farmers’ markets have a presence extending so far back in history. Before the transportation and refrigeration of goods became accessible, communities were far more intertwined with surrounding farmlands. Growth in the urban areas resulted in concomitant growth in agriculture. As cities began to grow into areas previously used for agriculture, farmlands were pushed farther and farther away from the communities they served. Simultaneously, technological advances in storage and transportation opened up opportunities for farms to move even farther out. Grocery stores became an increasingly popular source for produce and goods as early as the 1700’s. In the most densely populated urban areas, farmers’ markets began to disappear and interests shifted to these stores, which offered more of both choice and convenience. Unfortunately, better roads and sustainable refrigeration soon ushered in the spread of supermarkets and wholesalers in all areas of the country, not just the cities. Many small farms and markets were cut out of the food cycle. Shortly after WWII ended, there were only 6 markets in the entire state of California. Luckily, the 1960s and 70s saw an America which was becoming more health-conscious. With a cultural shift away from mass production and mass consumption, farmers’ markets began to appear again. Fresh, healthy, and easy-to-prepare foods became more of a priority for families. And nostalgia played a factor, as the public remembered the quaintness of farmers’ markets, their sense of community and the access to fresh foods they provided. Farmers’ markets experienced explosive growth between 1994-2008. While that growth has definitely leveled off, there are 8500+ markets in the U.S. and $1.1 billion dollars is spent at them annually. A billion dollar business where the practices are a net positive for everyone involved.  By Contributing Writer; Aimee Whittington Ph.D. After the last 2 market seasons, it’s become even more apparent that the Amherst Farmers’ Market is more than simply a place to purchase food. For many, it was the only (or one of a very few) opportunity they had to interact with other people. So as the 2022 season rapidly approaches for the AFM, we’re looking at continuing to strengthen the market’s engagement with the local community. One of the most common ways farmers’ markets engage is through consumer education. A chef’s stage or other live cooking event, guided market tours and cross promotion strategies between vendors are all tools which can draw customers in, while also providing knowledge and agency for the shopper. As the public becomes increasingly interested in local food, education provides a double win because it both draws in customers and equips them with new knowledge to combat food insecurity. Social media is another tool markets can use to foster community engagement, especially among younger consumers. Using it for advertising and education is an efficient way to reach a larger number of people. Postings include a mix of short and long form articles, videos, recipes and local news stories. Special events can be important for bringing markets greater exposure and bring new customers. Additionally, these events have been cited as a way to attract low income customers who often feel like a farmers’ market is an exclusive place. They present no obligation to spend money and offer something fun for young children. Monthly “festivals” and events based around a specific product - tomato time, for example - are by far the most popular approaches taken by markets. A once a month special event strikes a balance where it’s regular enough customers will remember it takes place but not so often the event doesn’t feel special. For instance, with tomato time, a market might do a tomato tasting and provide recipes and nutritional information. Lastly, kid’s activities and engagement can attract younger people, making them familiar and comfortable in the market. Which is important because in 10 years, those children will be the household grocery shoppers. Additionally, the more entertained the children of customers are, the longer the shopping experience will take. This is another double win for the vendors and the community. The longer people stay, the more they tend to purchase but also, hopefully, the more opportunities the Amherst Farmers’ Market has to continue strengthening the community. With only 3 months before the first 2022 AFM, the market staff is very much looking forward to finding new ways to strengthen the bonds with customers we have and forge new ones with customers we don’t have, yet. Building on the momentum of the last 2 difficult but very successful seasons, we look forward to making it the 51st season even better.  By Contributing Writer; Aimee Whittington Ph.D. A "food desert" is defined as a geographic area where access to affordable, healthy food options - especially fresh fruits and vegetables- is restricted or nonexistent due to the absence of grocery stores within easy traveling distance. According to a report prepared for by the Economic Research Service of the USDA, about 19 million people in the US reside in a food desert, with 2.5 million of them residing in Massachusetts. In urban areas, access to public transportation can help residents overcome the difficulties posed by distance, but economic forces have driven grocery stores out of many cities in recent years, making them few and far between and an individual’s food shopping trip may require taking several buses or trains. In suburban and rural areas, public transportation is either very limited or unavailable, with supermarkets often many miles away from people’s homes. The other defining characteristic of food deserts is socio-economic: that is, they are most commonly found in BIPOC communities and low-income areas, where many people don’t have cars. Studies have found that wealthy districts have three times as many supermarkets as poor ones do, that white neighborhoods contain an average of four times as many supermarkets as predominantly black ones do, and that grocery stores in African-American communities are smaller with less selection. People’s choices about what to eat are severely limited by the options available to them and what they can afford—and many food deserts contain an overabundance of fast food chains selling cheap “meat” and dairy-based foods that are high in fat, sugar and salt. Processed foods (such as snack cakes, chips and soda) typically sold by corner delis, convenience stores and liquor stores are usually just as unhealthy. Communities that are located in food deserts are often overlooked when relying on data collected by the US government. Part of the problem is how the US government’s Industry Classification System categorizes retail outlets that sell food. According to the NAICS code, small corner grocery stores are statistically lumped together with supermarkets, such as Safeway, Whole Foods Market, etc. In other words, a community with no supermarket and two corner grocery stores that offer liquor and food would be counted as having two retail food outlets even though the food offered may be extremely limited and consist mainly of junk food. Those living in food deserts may also find it difficult to locate foods that are culturally appropriate for them, and dietary restrictions, such as lactose intolerance, gluten allergies, etc., also limit the food choices of those who do not have access to larger chain stores that have more selection. Additionally, studies have found that urban residents who purchase groceries at small neighborhood stores pay between 3 and 37 percent more than suburbanites buying the same products at supermarkets. To address this problem locally, many communities have started mobile farmers’ markets. The Amherst Mobile Market was started in the summer of 2020. It makes affordable produce available within walking distance of residents who would otherwise struggle to access healthy food. Additionally, it allows low income and BIPOC community members to retain agency over their decision making. Challenges around food access in Amherst are always extant for some but most people don’t know nearly all of Amherst's census tracts are designated as food deserts by the USDA. Residents without vehicles represent 11% of Amherst's population and it can take over two hours to get to and from the grocery store by bus. Over 2 dozen residents, all residing in food deserts, participated in the planning process and the market employed 14 Amherst residents in 202 and 2021. There are over a dozen local small farms participating and for $5 a week, customers get a 6 item ‘farmshare’. The cost of which is reimbursable through the Healthy Incentives Program, if the SNAP benefit is used. Food insecurity and food deserts are two very real problems facing far too many people today. Fortunately, through continued innovations of programs like the Healthy Incentives Program and the Amherst Mobile Market, and LOCAL outlets like the Amherst Farmers' Market, it’s one that’s being addressed.  By AFM Contributing Writer; Aimee Whittington, Ph.D. With respect to the Amherst Farmers’ Market, one positive development to come out of the last 2 years is the increased diversity of the market’s customer base. Not only did the pandemic bring out a much younger demographic, as seen by the large number of college students shopping from 10 a.m. until breakdown, it also sparked a resurgence in overall community interest in direct to consumer food sales. Additionally, the market saw an increased usage of one of the nation’s most innovative programs designed to address food insecurity and healthy food access - the Healthy Incentives Program (HIP). HIP is a program administered by the Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance and funded through a combination of federal funds, state funds and private contributions. For market customers who are enrolled in the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP - formerly known as food stamps), HIP ‘rewards’ recipients with extra benefits when they use SNAP to purchase fruits, vegetables, and certain plants at farmers markets, farm stands, CSAs. HIP is the first program of its kind established in the U.S. Depending on household size, Massachusetts’ HIP funds match SNAP benefits dollar-for-dollar: By using HIP, SNAP recipients can earn back up to: ● $40 monthly (for 1 – 2 people) ● $60 monthly (for 3 -5 people) ● $80 monthly (for 6+ people) Massachusetts has historically done groundbreaking work, with regards to local and direct marketed agriculture and food insecurity. In 2006, The Food Project’s Lynn Central Square Farmers’ Market became one of the first in the country to accept SNAP benefits electronically/They also piloted a small SNAP matching program. Two years later, this small program served as a model for the Boston Bounty Bucks program, a dollar-for-dollar matching program for use at Boston-area farmers’ markets. This program demonstrated the demand generated by SNAP-matching for consumers and expanded the opportunity for Massachusetts farmers to sell their harvests locally. These two programs served as the precursor and inspiration for the Healthy Incentives Program, which launched statewide in 2017. In that first year, HIP helped over 36,000 families gain access to farm-fresh produce. By 2019, that number had grown to 19,000 households per month utilizing the benefit. For individual recipients, HIP is only a positive. It increases access to fresh, local produce and helps stretch SNAP dollars without extra paperwork. It rewards recipients for buying local produce at designated locations. Lastly, it allows SNAP recipients to grow their own fruits and vegetables, if they choose, by purchasing food-producing plants and seeds. It’s also a boon to local producers. For the state economy, HIP has provided Massachusetts farmers with more than $15 million in revenue. It has served to broaden the customer base for many small, local farms struggling to increase revenue and continues to do so. Most importantly, HIP has allowed access to products which were historically too expensive for customers on a restricted budget. Everyone should be able to feel the juice of a peach on their chin or smell the ‘summer’ of a tomato as they slice it. HIP is allowing people to do just that.  By AFM Contributing Writer; Aimee Whittington Ph.D. In addition to the COVID necessitated changes of the last two years, the agricultural industry has been navigating extreme changes caused by multiple factors over the last decade. Demographic, social, technical, and economic developments have led to the modern industrialized model of food agriculture. Large scale farms and food processing firms dominate production and both they and supermarket chains dominate distribution. The food supply chain has been growing increasingly globalized for decades. As society and economic systems evolved, so did the needs of the consumer and their buying behaviours. Urbanization is one of the main factors that distance the places of production from those of consumption. Accordingly, a growing number of connections (transport, storage, packaging, processing) must be carried out by a plurality of actors. This results in producers having to achieve economies of scale and cut production costs. The most effective way to accomplish this, within the industrialized model of provisioning, is for farms to specialize on only a few products and/or specific phases of the production. The results of these adjustments resulted in the elimination of direct delivery to final consumers and of processing products on-farm. The industrialized model of agriculture is highly efficient, especially as compared to previous models of organising production and distribution. This explains why this model has spread and is dominant at world level. Unfortunately, the agricultural community is now learning how damaging it can be. Among the concerns and criticisms raised are potential danger to food safety, decreased nutritional access, environmental pollution and under many points of view, prevention of market access to smallholders and small and medium enterprises. Over the last decade, with the most rapid evolution taking place over the last 2 years, changes have been made which are swinging the pendulum back towards the local farmer. Short food supply chains have been making a comeback. A short food supply chain (SFSC) is characterized by short physical distance and/or involvement of few, if any, intermediaries between producers and consumers. Examples include farmers’ markets and CSAs, Most specifically, they address functions the industrialized model seems unable or unwilling to provide. The positive changes seen when short food supply chains are put into place and/or strengthened from enhancing SFSCs already in existence affect producers and consumers. In addition to the financial benefits provided to the producers and the far more secure supply chain for the consumer, SFSCs provide a host of other benefits. They strengthen social relations, preserve the environment, improve nutritional aspects of many foods, and enhance local development. Additionally, shortened food chains are extremely useful in sustainable development practices. Expected effects of SFSC growth include continued increases in responsible production and consumption, with regard to land and local resource management, and the meeting of sustainable development goals related to social issues. The two most directly affected being poverty and hunger reduction and enhanced gender equality. SFCS also contribute to the sustainable development goals of addressing climate change and its impacts, as well as that of making communities (especially urban areas) more inclusive, safe, and resilient. As we’ve seen firsthand over the last 2 years, the positive impacts of short food supply chains are difficult to overstate. Sustained economic growth of SFSCs, as evidenced by increased income generation, job opportunities and the building of inclusive production capacities demonstrate they are an effective strategy for producers to consider moving forward. Given the current uncertainty, increased community connections, easy access to safe and healthy food and stable supply chains are just as important now as they were at this time in 2020. The ability to remain resilient in front of global market disruption and providing net positives at every step of the process might be a singularity. Being able to watch it unfold at the Amherst Farmers’ Market has been an astounding experience.  By AFM Contributing Writer; Aimee Whittington Ph.D. The state of Massachusetts has 500,000 acres of farmland holding 7200 farms. The state’s agricultural industry produces an annual market value of nearly half a billion dollars and provides direct employment to 26,000 people. The average farm in Massachusetts annually produces $66,000 worth of agricultural products on just under 70 acres. Simply because of geography, small farm culture - especially family farming - is prevalent in New England agriculture and Massachusetts is no exception. Small farms with agricultural sales below $100,000 a year account for 85% of farms in the state. And 80% of those are owned by a single family or individually. And rounding out the demographics, the average age of a Massachusetts single operator is 59 and 38% of all principal operators are women. One of the biggest facets of small farm culture is the farmers’ market. Direct market sales is a key feature of Massachusetts agriculture. Market venues provide growers and producers opportunities to engage in direct marketing. Or the face to face sale of their products to the end consumer, with no intermediary retailers. And make no mistake, those small-scale, individual interactions add up to big business. Nationwide, in the 20 year period from 1994 to 2014, the number of farmers’ markets in the USDA directory increased 370%, from 1,755 to 8,268. From 2015 until now, the number of markets rose slightly. Growth had begun to even out, with the last 2 years seeing a spike due to the pandemic. Massachusetts ranks 5th in the nation for direct farmers’ market sales with over $100 million generated annually. Direct market sales account for 21% of the state’s total agricultural product revenue, which is the highest proportion in the country. Additionally, Massachusetts is 3rd in the country for direct sales per farm ($55,384) and 8th in the nation for direct sales per capita. The Amherst Farmers’ Market was established in 1971 and has brought (preCOVID) several thousand shoppers into the town center every Saturday for many of those years. When the pandemic hit in early 2020, there was concern as many farmers’ markets across the country were cancelled. Luckily most reopened sooner rather than later, with many having to adapt to rapidly changing state and/or local guidelines. Market runners had to find creative ways to source supplies, such as bathroom facilities and hand washing stations, and enforce policies which mandated masks, social distancing and other precautions. Because instead of slowing down, business at markets (especially those held outdoors) was growing rapidly. Concerns about shopping for food safely, in combination with disrupted grocery store supply chains, caused consumer interest in locally sourced food to skyrocket. Market vendors and managers had to adapt quickly. There was a steep learning curve for some, as technology was put into place for options like pre-ordering, pre-packaging and curbside pickup. More affluent shoppers either became interested in or reinvested in buying local food. Lower-income buyers were able to use enhanced federal benefits such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. As well as having access to a program in Massachusetts which provides limited matching funds for purchases of fresh produce, the Healthy Incentive Program. The pandemic brought young people out to our market in previously unseen numbers. Every facet of the market has undergone substantial change. For producers, managers and consumers filling these new and expanded roles has been no mean feat and the future is not yet certain. However, these last 2 years have shown us our marketplace responds vigorously to crises, while continuing to create growth and opportunities.  By AFM Contributing Writer: Cheryl Conklin Maintaining a Profitable Hobby Farm Hobby farms can be a fun, lucrative venture for those willing to put in the effort. Learn more about how you can earn an income from your hobby farm. Attending Farmers' Markets Farmer's markets have seen a rise in popularity in recent years, and Amherst is home to many of them. Having a dedicated place at a farmers' market means you'll be exposed to many potential customers and you can make face-to-face connections as you pitch your product. Do your best to have a consistent presence at these farmers' markets. Many customers may plan their meals around visits to your stall, and you'll earn their trust by showing up regularly with the products they want. And, ask for feedback on your products and solicit suggestions for future offerings. Invite Guests to Your Farm Your land itself can also be a valuable profit source. You can effectively create two distinct income streams: product and property. By creating a brand for your property, you can sell the experience of visiting in addition to the actual products. Many people may be interested in learning how to grow their own produce or butcher their own meat, and hosting on-site workshops on these topics can entice them to visit your farm. If you have the space, also think about hosting events, such as weddings, or renting out your farm for others to host events. Make sure you consult a Massachusetts business law attorney who can help you understand the risks and liabilities involved with inviting the public to your working farm. Using Social Media Marketing Social media is a powerful tool for connecting with potential customers. Customers will be able to discover your business and you can develop a devoted following through regular and meaningful interaction with customers on social media. You can start by following other hobby farm accounts to see what types of content they're posting. This will give ideas for content for your own account and you'll be able to judge what content is most popular and engaging. However, be sure to practice proper social media etiquette, which includes asking for permission or giving credit when sharing someone else's content. As video platforms such as TikTok continue to dominate social media, make sure you get comfortable being on camera. If it helps, you can create a script for your videos and set up a content creation schedule to make the process less overwhelming. You can also hire a social media manager to help you market your business. You can find these professionals on freelance platforms, and you should account for turnaround time and client reviews. And if you just asked “How much do social media managers make?” then it’s important to budget for between $14 and $35 per hour. Lead with Locally Sourced In a crowded field of products, one of your main selling points will be your homegrown appeal. Consumers are increasingly interested in locally-sourced foods and there is a growing movement to embrace the farm-to-table concept. Advertising yourself as a locally owned organic business can also prove to be profitable around the holidays as many people intentionally look to check off their holiday shopping lists with products from local small businesses. Profiting Off Your Hobby Farm Not only can your hobby farm provide sustenance for your family, but it can also generate a sustainable income. Monetizing your hobby farm can be done in many ways and through many outlets; selling from a local farm stand or building your own. Selling to local merchants that are willing to add value with your product. Visiting and joining local farmers' markets in your area like many sellers do in Amherst at the Amherst Farmers' Market!  By AFM Contributing Writer: Aimee Whittington Ph.D. One of the industries most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic over the last 2 years has been agriculture. Smallholders produce over 1/3 of the world’s food and, globally, the food supply rests quite literally on their shoulders. In fact, so many farms are run by only one person or one family, most countries asked farmers to provide written instructions on farm operations, in case they contracted COVID. In the United States, 80% of the 2.02 million farms are classified as ‘small’, with a gross income of less than $100,000. Most of that income is derived from selling to stores, schools and restaurants in the producer’s general area. When schools and restaurants shuttered in 2020, many farmers were stuck with extra inventory and nowhere to sell it. While large chain grocery stores were selling out and resources like food banks were overwhelmed, those local farmers had to choose a next step. After the initial impact died down, small farmers overwhelmingly turned to their communities. And many found success by shifting their business models. Most of those small farms pivoted in one of two ways. First, some transitioned to, or became exclusively, a ‘closed loop food system’. That’s when a single farm controls the entire food chain. Everything is grown/raised and harvested/butchered on the farm. Then it’s packaged at and sold by the farm. The closed loop system insulates against most of the supply chain issues caused by the pandemic. Second, while the pandemic certainly reduced some types of demand, it created others at a local level. These local buyers gave many small farms a chance to switch operating models. It worked especially well for farms with CSAs. The disruptions in the supply chain combined with so many people wanting a ‘safer’ source of food and ‘safer’ place to shop, resulted in CSA memberships increasing substantially across the country. Additionally, farms running CSA's were able to look at products which had historically sold well and produce more of those products for local customers. Lastly, the community value of a market (especially in the open air), can’t be overstated. Especially for those who are high risk or couldn’t, until recently, ensure the safety of small children, farmers’ markets provide an invaluable point of connection. They provide a touchstone of normalcy in a world still too full of uncertainty. Bringing together local producers, local folks and fostering community engagement has, quite possibly, never been more important. We need the small farms. We need the markets. We need each other. One of the things that makes the Amherst Farmers’ Market special, is the focus on keeping the small farmer at its center. For all of us, navigating the market through the summer of 2020 was both an exhausting and an immensely rewarding experience. The summer of 2021 was slightly easier because we had some idea of what we needed to do. Over the next several newsletters, we’re going to take a more detailed look at the changing landscape of the small farm, with emphasis on Massachusetts. As we get ready for the 2022 season, whatever it may bring. Happy New Year's! |

AFM Marketblog

Bringing you organic, grass-fed, pasture-raised, locally-sourced blog posts on a semi-weekly basis from the Amherst Farmers' Market. Archives

July 2022

categories...

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed